It is generally assumed -by most British historians- that the tribes of Scotland remained completely autonomous, with the nationalistic notion of ancient Caledonian tribes holding firm against the might of the Roman war machine. But archaeological evidence has shown that the low-land regional boundaries moved several times, with many annexed tribes becoming subject to Roman rule for a time.

Even if northern Caledonia was occupied only for some decades, the southern Caledonia area near the Hadrian Wall was occupied for centuries and was also a roman province: the "Valentia provincia" (located between the Antonine Wall and the Hadrian Wall).

|

| Map of Roman Britannia showing the "Valentia" province |

Even if northern Caledonia was occupied only for some decades, the southern Caledonia area near the Hadrian Wall was occupied for centuries and was also a roman province: the "Valentia provincia" (located between the Antonine Wall and the Hadrian Wall).

Indeed incursions into central and northern Caledonia established chains of fortifications such as the Gask Ridge (built between 70-80 AD) and exploratory marching camps encircling the Fife, Angus, Tayside, Crampians and stretching as far north as the Moray Firth (next to the modern city of Inverness) in the successive decade. The same happened again more than a century later under emperor Septimius Severus.

Additionally it is noteworthy to remember that during the Roman invasion of Britain the "King of Orkney" was one of 11 British leaders who is said to have submitted to the Emperor Claudius in AD 43 at Colchester (called Camulodunum in latin). What we don't know is the exact extension of the territory controlled by this king, who successively was probably- as Romans used to do in this situations- the ruler of a possible "client-kingdom" of the Roman empire in northern Caledonia. Agricola in autumn 84 AD sent a roman fleet to take control of the Orkney islands and possibly of the northern tip of Caledonia ruled by their king.

However there is certainly evidence of an Orcadian connection with Rome prior to AD 60 from pottery found in the Orkney islands at the Broch of Gurness (and 1st and 2nd century Roman coins have been found at Lingro Broch). Furthermore In a late document ("Nomina Omnium Provinciarum" of Polemius Silvius, Laterculus II), the Roman historian Polemius Silvius listed all the Roman provinces, including the Diocese of Britannia: (Britannia) Prima, (Britannia) Secunda, Maxima, Flavia, Valentiniana (in southern Caledonia), and the name of the 6th hypothetical province called Orcades (Orkneys) in the northermost area of Caledonia. Although the name of latter in Polemius’ list has been considered by Mommsen as an interpolation added subsequently (Eutropius, 7.13), new Roman archaeological finds from Mine Howe, Mainland, Orkney, might represent the evident clue for a different interpretation of the late Roman source. (read https://www.academia.edu/33336307/Orkney_the_6th_province_of_Britannia_New_evidences_from_Mine_Howe).

So, we can resume the presence of Rome in areas of actual Scotland within these years:

1) southern Caledonia: more than 3 centuries, mainly near the Hadrian Wall (romanised "Habitancum" survived from Agricola times until the first decades of Sub-Roman Britannia).

2) central Caledonia: many decades, around the Antonine Wall (Cramond castrum -the Roman Edinburg- was created around 135 AD and abandoned only after the Septimius Severus withdrawal in 215 AD).

3) northern Caledonia: some years, from the Gask Ridge until the Cawdor castrum near actual Inverness (Inchuthil castrum lasted nearly ten years).

4) northermost tip of Caledonia and the Orkney islands: a possible period when was created the hypothetical "Orcades provincia", but until now nothing is sure about the existence of this late Roman province (read also: http://researchomnia.blogspot.com/2019/11/orkney-possible-6th-province-of-roman.html ).

The invasions

Additionally it is noteworthy to remember that during the Roman invasion of Britain the "King of Orkney" was one of 11 British leaders who is said to have submitted to the Emperor Claudius in AD 43 at Colchester (called Camulodunum in latin). What we don't know is the exact extension of the territory controlled by this king, who successively was probably- as Romans used to do in this situations- the ruler of a possible "client-kingdom" of the Roman empire in northern Caledonia. Agricola in autumn 84 AD sent a roman fleet to take control of the Orkney islands and possibly of the northern tip of Caledonia ruled by their king.

However there is certainly evidence of an Orcadian connection with Rome prior to AD 60 from pottery found in the Orkney islands at the Broch of Gurness (and 1st and 2nd century Roman coins have been found at Lingro Broch). Furthermore In a late document ("Nomina Omnium Provinciarum" of Polemius Silvius, Laterculus II), the Roman historian Polemius Silvius listed all the Roman provinces, including the Diocese of Britannia: (Britannia) Prima, (Britannia) Secunda, Maxima, Flavia, Valentiniana (in southern Caledonia), and the name of the 6th hypothetical province called Orcades (Orkneys) in the northermost area of Caledonia. Although the name of latter in Polemius’ list has been considered by Mommsen as an interpolation added subsequently (Eutropius, 7.13), new Roman archaeological finds from Mine Howe, Mainland, Orkney, might represent the evident clue for a different interpretation of the late Roman source. (read https://www.academia.edu/33336307/Orkney_the_6th_province_of_Britannia_New_evidences_from_Mine_Howe).

So, we can resume the presence of Rome in areas of actual Scotland within these years:

1) southern Caledonia: more than 3 centuries, mainly near the Hadrian Wall (romanised "Habitancum" survived from Agricola times until the first decades of Sub-Roman Britannia).

2) central Caledonia: many decades, around the Antonine Wall (Cramond castrum -the Roman Edinburg- was created around 135 AD and abandoned only after the Septimius Severus withdrawal in 215 AD).

3) northern Caledonia: some years, from the Gask Ridge until the Cawdor castrum near actual Inverness (Inchuthil castrum lasted nearly ten years).

4) northermost tip of Caledonia and the Orkney islands: a possible period when was created the hypothetical "Orcades provincia", but until now nothing is sure about the existence of this late Roman province (read also: http://researchomnia.blogspot.com/2019/11/orkney-possible-6th-province-of-roman.html ).

|

The invasions

In the summer of 84 AD, an army of 30,000 Caledonian warriors faced off against the 20,000 strong Roman invasion force led by General Gnaeus Julius Agricola at the Battle of Mons Graupius. According to the Roman historian Publius Cornelius Tacitus, 10,000 Caledonian lives were lost at the cost of less than one thousand Roman legionaries and their auxiliary troops.

This resulted in the proclamation that Agricola had finally subdued resistance to Roman rule across all the territories of Britain. A brief period of some winter months of “Romanisation” now occurred as a roman fleet reached the Orkney & Shetland islands (where the "king of Orkney" had previously submitted to emperor Claudius in 48 AD) and the lowland territories saw a series of construction projects, roads and infrastructure that would have been the foundations of a new Roman province. Agricola took some hostages as a warranty of submission from the defeated Caledonians and went to the newly built Inchtuthill castrum (in the Gask Rigde area) to wait for the next spring.

It is likely that Rome had intended to continue campaigning and expand the fully controlled borders of Britannia to the western Caledonian coast's islands and even in what is now Ireland, but Rome recalled Agricola because further military requirements elsewhere in the empire necessitated a troop withdrawal.

Tacitus’ statement on his account of the Roman history between 68 AD and 98 AD: “Perdomita Britannia et statim missa” “Britain was completely conquered and immediately let go” in 85 AD, denotes his bitter disapproval at the failure to unify the whole Britannia island under Roman rule (after Agricola’s successful campaigning in Caledonia) and create a roman province of Caledonia.

Tacitus’ statement on his account of the Roman history between 68 AD and 98 AD: “Perdomita Britannia et statim missa” “Britain was completely conquered and immediately let go” in 85 AD, denotes his bitter disapproval at the failure to unify the whole Britannia island under Roman rule (after Agricola’s successful campaigning in Caledonia) and create a roman province of Caledonia.

In later years, the frontier of the Roman territory and Caledonia was fixed south of the Cheviot Hills by the Emperor Hadrian with the construction of Hadrian’s Wall in 122 AD. The frontier was moved further north around 142 AD when the Antonine Wall was built between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde (west of Edinburgh along the central belt of Scotland).

The Romans retreated to Hadrian’s Wall a decade later but reoccupied the Antonine wall temporarily in 208 AD under the orders of Emperor Septimius Severus (this has led to the wall being referred also as the "Severan Wall").

Roman historian Cassius Dio wrote ( http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/77*.html ) that "Severus did not desist until he approached the extremity of the island. Here he observed most accurately the variation of the sun's motion and the length of the days and the nights in summer and winter respectively."

So, while Agricola sent his fleet to the top of Britannia, Septimus Severus was able to arrive personally to the northernmost area of the British isles, but his illness forced him to retreat to the southern Caledonia. There he signed a temporary peace with the Picts, forcing them to surrender to Rome most of their territory. What we don't know is where exactly he arrived, when "he approached the extremity of the island".

Probably it was the area of Muiryfold (where has been discovered a huge Roman castrum of 120 acre: https://canmore.org.uk/site/17346/muiryfold ) near the Moray Firth, but could have been more to the north because recently have been discovered in Portmahomac (see following map) what seems to be a Roman camp.

However the Caledonians started new raids and Septimius got enraged, ordering a "total war" against them. He wanted to conquer all Caledonia (including the western Atlantic islands) but died in 211 AD. His son Caracalla (after an initial attack against the Picts) decided to withdraw to the Hadrian Wall and -after signing a new peace agreement with the Picts- went to fight in other areas of the Roman empire where there was a more dangerous situation.

With the exception of some minor border skirmishes, a period of peace was established along this frontier that lasted for more than a century: this was an evident consequence of the bloody Severus campaigns, that greatly weakened the Caledonians.

|

| Map showing the Roman roads (like Dere street) officially discovered in actual Scotland and some of the main Roman fortifications (Inchtuthil, Trimontium, Cramond, Habitancum) in Caledonia |

So, while Agricola sent his fleet to the top of Britannia, Septimus Severus was able to arrive personally to the northernmost area of the British isles, but his illness forced him to retreat to the southern Caledonia. There he signed a temporary peace with the Picts, forcing them to surrender to Rome most of their territory. What we don't know is where exactly he arrived, when "he approached the extremity of the island".

Probably it was the area of Muiryfold (where has been discovered a huge Roman castrum of 120 acre: https://canmore.org.uk/site/17346/muiryfold ) near the Moray Firth, but could have been more to the north because recently have been discovered in Portmahomac (see following map) what seems to be a Roman camp.

| Map I have created for Wikipedia, showing the last discovered Roman fortifications in northern Scotland |

However the Caledonians started new raids and Septimius got enraged, ordering a "total war" against them. He wanted to conquer all Caledonia (including the western Atlantic islands) but died in 211 AD. His son Caracalla (after an initial attack against the Picts) decided to withdraw to the Hadrian Wall and -after signing a new peace agreement with the Picts- went to fight in other areas of the Roman empire where there was a more dangerous situation.

With the exception of some minor border skirmishes, a period of peace was established along this frontier that lasted for more than a century: this was an evident consequence of the bloody Severus campaigns, that greatly weakened the Caledonians.

During this time the tribes to the north of the wall were left unmolested and united to form the Pictish nation. The Picts’ name first appears in 297 AD and comes from the Latin Picti, meaning ‘painted people’.

By 306 AD however (when the Picts were united and better organized) the Emperor Constantius Chlorus was forced to protect his northern frontier against Pictish attacks on Hadrian’s Wall.On several fronts throughout Europe the tide was slowly turning against the mighty Roman Empire.

As Rome weakened the Picts became bolder, until in 360 AD together with the Gaels from Ireland they launched a coordinated invasion across Hadrian’s Wall. The Emperor Julian dispatched legions to deal with them: they were defeated by Count Theodosius (the father of emperor Theodosius the Great) but with little lasting effect.

Following the final retreat to Hadrian’s Wall around the first years of the fifth century, incursions by the Romans were generally limited to scouting expeditions in the buffer zone that developed between the walls, trading contacts, bribes to purchase truces from the natives, and eventually the further spread of Christianity.

The surviving archaeology (that includes the countless forts, marching camps and around 400 miles of roads across the Scottish landscape) has given archaeologists a valuable glimpse into a militaristic approach to subdue a native population, rather than the less forceful techniques of Romanisation applied in the rest of Britannia through building works, Christianization and cultural assimilation.

The Roman archaeological evidences in Caledonia

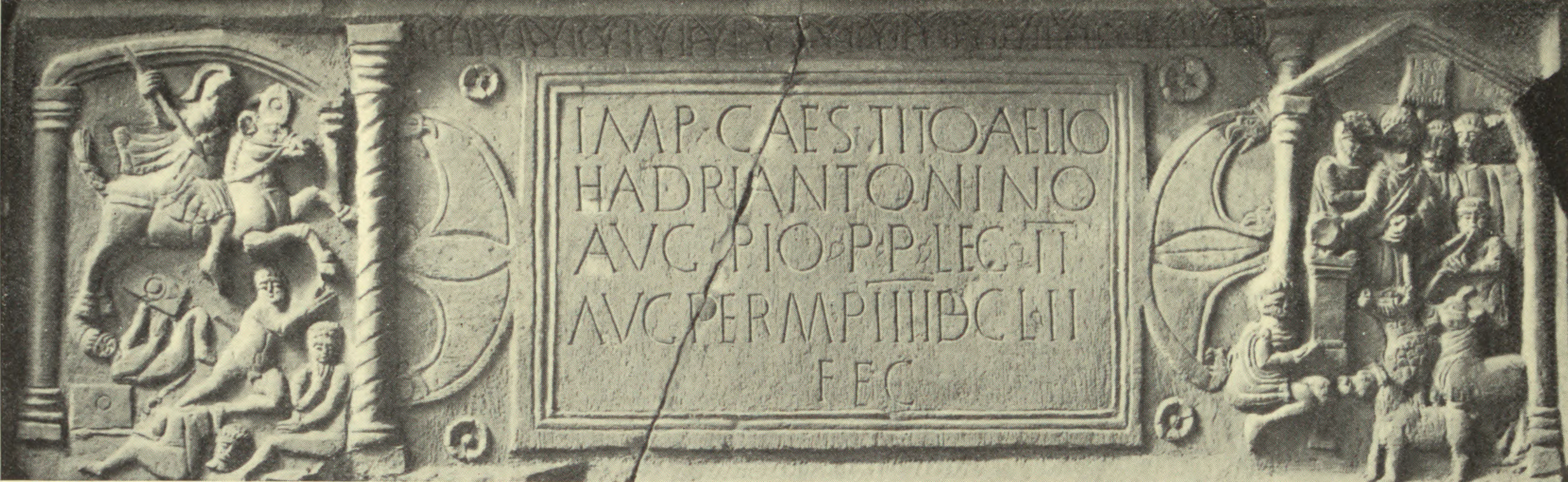

The most famous evidences of Roman presence north of the Hadrian Wall are those found in the area of the Antonine Wall: the "Summerstone Slab" and the "Bridgeness slab" are some of the most important. .

|

| The "Bridgeness slab" (see video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lXg8H2zzyC4) |

The Summerston slab was found on a farm near Glasgow around 1694, while the Bridgeness Slab was discovered in 1868 near the town of Falkirk, at the eastern end of the Antonine Wall (not far away from the Roman Edinburg).

Both slabs reproduce macabre scenes of Roman knights who ride against the indigenous warriors of the north and watched over captured and tied groups. A decapitated warrior is also reproduced in the middle of the battle in Bridgeness Slab. The two ends of the neck have red pigments, to symbolize the blood spilled in the execution. Even the beak of the eagle (the symbol of Rome and its legions), shows traces of red pigments to symbolize how Rome feeds on the body of its enemies.

On the plate of Summerston, moreover, to the dedication to the emperor Antoninus Pius, the Roman eagle is also represented which leans on the figure of a Capricorn, the symbol of the Second Legion of Rome who defended the Antonine Wall in that area.

But there are also two archaeological evidences in the area of Cramond, the Roman Edinburg: the "Cramond eagle" and the "Eagle rock". Cramond area is a sleepy coastal suburb of Edimburg today but in the second century AD the fort there was the Romans' largest military settlement in Scotland.

At this time, around 140 AD, the site of Edinburgh Castle today was occupied by a tribe called the Goddodin, known to the Romans as the Votadini.

The Goddodin were known to be allied to the Romans: historian Montesanti wrote that they had a capital (the famous "Traprain Law", located on a hill some miles east of Cramond castrum) that was the main center of a small "client kingdom" of Rome in eastern coastal southern Caledonia.

In the Traprain hill it was discovered a hoard of silver plate (consisting of over 24 kg - 53 lb- of sliced-up Roman era silver; see photo to the right showing silver cups and a triangular dish), showing a degree of huge romanization and cultural assimilation to the latin society.

53 lb- of sliced-up Roman era silver; see photo to the right showing silver cups and a triangular dish), showing a degree of huge romanization and cultural assimilation to the latin society.

Set between Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall, the location of Traprain placed it variously inside and outside the Roman Empire during the first few centuries AD, making the site pivotal to any understanding of Roman-native relations during this period. Despite some suggestions that Traprain may have been essentially a ritual centre during the Roman period, with only a very limited resident population, the recent archaeological work has tended to support the more traditional view of the site as a Roman 'boomtown'. For example, excavation of a steeply-sloping area of the inner rampart of the Traprain hill revealed that its collapsed remains were sealed by a deep accumulation of floor deposits, the uppermost associated with Samian roman pottery of the 2nd century AD. The use of such inconvenient, steeply sloping corners of the hill for the construction of buildings suggests that space may have been at a premium.

Indeed, one of the recurrent features of the researches has been the density with which Roman Iron Age activity is distributed across the Traprain hill...…. This Votadini capital, if such it was, may have been occupied by romanised inhabitants until the arrival of the Angles in or after the mid 7th century AD; more likely, given the excavated finds and the state of the surviving defences, it was mostly abandoned c. mid 5th century with power transfering further west, perhaps to Edinburgh (read "excavation accounts" of CANMORE https://canmore.org.uk/site/56374/traprain-law ).

Indeed a massive presence of Roman pottery in "Traprain Law" confirmed the presence of Roman settlers as first indicator of any Roman activity. A. Hogg (1951), reviewing Traprain Law in a Votadinian context, regards it as having been occupied by inhabitants on good terms with Rome up to about AD 155 after which it may have been temporarily abandoned (due to an attack on people friendly to Rome after the withdrawal of troops by Albinus). He thinks that the occupation was probably resumed after the Severan restoration and continued up to the 6th century, because it is listed as one of the places at which St Monenna founded there a church and because the multi-roomed houses can - by analogy with those at Ingram Hill (Northum 27 SW)- be considered post-Roman. Read for further information pg 15 of https://www.academia.edu/33336307/Orkney_the_6th_province_of_Britannia_New_evidences_from_Mine_Howe .

Some historians suggest that Edinburgh's Dalkeith Road is a remaining section of Dere Street, the road built by the Romans to connect their settlements north of the border with York (the Roman "Eburacum"). Running through the south side of the city, the road then branched westwards along the edge of an ancient lake along the line of modern-day Melville Drive. It then ran out to the fort at Cramond, built on the edge of a natural harbour on the shores of the Firth of Forth.

The Antonine Fort from AD 139 was probably built for the second invasion of Scotland, but was destroyed in 197AD. Severan Fort built on the same site, but differently alined about 205/208 AD. The rebuilding of the fort would have been part of a major refurbishing of the Wall undertaken in the first years of the third century.

The visible remains at Habitancum are of a fort constructed in the early years of the third century AD by the Emperor Severus; an inscribed slab, uncovered by excavation, records the construction of the fort by a 1000 strong mounted cohort (one of the ten units of a Roman legion). The walls of the fort are substantial features up to 10m wide and standing to a height of 0.5 to 1.2m above the interior of the fort.The remains of the internal Roman buildings are thought to lie beneath this later settlement; partial excavations in the 1840s revealed the layout of the bath house situated in the south east angle of the fort and a headquarters building situated at the centre of the fort.

Excavations also uncovered early second century pottery and evidence of burning beneath the present western rampart; this has been taken to suggest that the present visible remains resulted from the reconstruction of an earlier 2nd century fort built under the Emperor Antoninus Pius and probably destroyed during the invasions of northern tribes recorded in the late second century AD. Some historians think that Habitancum was historically very important because it was the capital of the "Valentia provincia", created by Count Theodosius in the fourth century and populated by romanised Britons with some Roman citizens. The fort is believed to have been definitively destroyed around 397 AD, but the vicus remained inhabited until the first decades (and probably beyond) of the Sub-Roman period in the fifth century.

Both slabs reproduce macabre scenes of Roman knights who ride against the indigenous warriors of the north and watched over captured and tied groups. A decapitated warrior is also reproduced in the middle of the battle in Bridgeness Slab. The two ends of the neck have red pigments, to symbolize the blood spilled in the execution. Even the beak of the eagle (the symbol of Rome and its legions), shows traces of red pigments to symbolize how Rome feeds on the body of its enemies.

On the plate of Summerston, moreover, to the dedication to the emperor Antoninus Pius, the Roman eagle is also represented which leans on the figure of a Capricorn, the symbol of the Second Legion of Rome who defended the Antonine Wall in that area.

But there are also two archaeological evidences in the area of Cramond, the Roman Edinburg: the "Cramond eagle" and the "Eagle rock". Cramond area is a sleepy coastal suburb of Edimburg today but in the second century AD the fort there was the Romans' largest military settlement in Scotland.

At this time, around 140 AD, the site of Edinburgh Castle today was occupied by a tribe called the Goddodin, known to the Romans as the Votadini.

The Goddodin were known to be allied to the Romans: historian Montesanti wrote that they had a capital (the famous "Traprain Law", located on a hill some miles east of Cramond castrum) that was the main center of a small "client kingdom" of Rome in eastern coastal southern Caledonia.

In the Traprain hill it was discovered a hoard of silver plate (consisting of over 24 kg -

53 lb- of sliced-up Roman era silver; see photo to the right showing silver cups and a triangular dish), showing a degree of huge romanization and cultural assimilation to the latin society.

53 lb- of sliced-up Roman era silver; see photo to the right showing silver cups and a triangular dish), showing a degree of huge romanization and cultural assimilation to the latin society.Set between Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall, the location of Traprain placed it variously inside and outside the Roman Empire during the first few centuries AD, making the site pivotal to any understanding of Roman-native relations during this period. Despite some suggestions that Traprain may have been essentially a ritual centre during the Roman period, with only a very limited resident population, the recent archaeological work has tended to support the more traditional view of the site as a Roman 'boomtown'. For example, excavation of a steeply-sloping area of the inner rampart of the Traprain hill revealed that its collapsed remains were sealed by a deep accumulation of floor deposits, the uppermost associated with Samian roman pottery of the 2nd century AD. The use of such inconvenient, steeply sloping corners of the hill for the construction of buildings suggests that space may have been at a premium.

Indeed, one of the recurrent features of the researches has been the density with which Roman Iron Age activity is distributed across the Traprain hill...…. This Votadini capital, if such it was, may have been occupied by romanised inhabitants until the arrival of the Angles in or after the mid 7th century AD; more likely, given the excavated finds and the state of the surviving defences, it was mostly abandoned c. mid 5th century with power transfering further west, perhaps to Edinburgh (read "excavation accounts" of CANMORE https://canmore.org.uk/site/56374/traprain-law ).

Indeed a massive presence of Roman pottery in "Traprain Law" confirmed the presence of Roman settlers as first indicator of any Roman activity. A. Hogg (1951), reviewing Traprain Law in a Votadinian context, regards it as having been occupied by inhabitants on good terms with Rome up to about AD 155 after which it may have been temporarily abandoned (due to an attack on people friendly to Rome after the withdrawal of troops by Albinus). He thinks that the occupation was probably resumed after the Severan restoration and continued up to the 6th century, because it is listed as one of the places at which St Monenna founded there a church and because the multi-roomed houses can - by analogy with those at Ingram Hill (Northum 27 SW)- be considered post-Roman. Read for further information pg 15 of https://www.academia.edu/33336307/Orkney_the_6th_province_of_Britannia_New_evidences_from_Mine_Howe .

Some historians suggest that Edinburgh's Dalkeith Road is a remaining section of Dere Street, the road built by the Romans to connect their settlements north of the border with York (the Roman "Eburacum"). Running through the south side of the city, the road then branched westwards along the edge of an ancient lake along the line of modern-day Melville Drive. It then ran out to the fort at Cramond, built on the edge of a natural harbour on the shores of the Firth of Forth.

Few, if any, physical structures of the Roman fort at Cramond survive today, but the foundations of a huge network of buildings are marked out in the area adjacent to the medieval Cramond Kirk, a later church built on the site of the Roman encampment. Concealed beneath thick foliage lie the remnants of an immense Roman bathhouse, a major feature of Roman settlements.

The fort at Cramond was active during the period of construction of the Antonine Wall (around 140 AD), the defence built between Scotland's east and west coasts as a defence against the Picts: the Antonine Wall was constructed to keep the Roman forts -and civilian "vicus" around- safe from attacks from the north.

The size of the Roman encampment here, and the importance of the site as a militarily strategic river port, is reflected in some of the finds and archaeology which has been uncovered here. Beyond the traces of the buildings themselves, in 1997 the ferryman who ran a passenger service across the River Almond had to steer around what he thought was merely a rock jutting above the surface of the water. At low tide, however, the stone was examined and found be the tip of an immense carving of a lioness, a huge creative feature that archaeologists think may have been created as a grave marker or decorative tombstone for a significant general or military figure stationed at Cramond.

The "Cramond Lioness", as she is now known, has since taken pride of place in Edinburgh's National Museum on Chambers Street. Carvings like the lioness suggest that Cramond was established as a major, and permanent, settlement for the Romans. The fort was abandoned definitively only after the death of emperor Septimius Severus (who seems to have stationed briefly there) in 215 AD.

Some use of the fort (probably civilian) with minor building in a Roman manner also took place in the post-Severan period which may be associated with a little 4th c pottery. The civil settlement (vicus) was occupied also during the early Subroman period and probably was the first settlement of the medioeval city of Edinburg. Read for further information: https://canmore.org.uk/site/50409/cramond

The "Cramond Lioness", as she is now known, has since taken pride of place in Edinburgh's National Museum on Chambers Street. Carvings like the lioness suggest that Cramond was established as a major, and permanent, settlement for the Romans. The fort was abandoned definitively only after the death of emperor Septimius Severus (who seems to have stationed briefly there) in 215 AD.

Some use of the fort (probably civilian) with minor building in a Roman manner also took place in the post-Severan period which may be associated with a little 4th c pottery. The civil settlement (vicus) was occupied also during the early Subroman period and probably was the first settlement of the medioeval city of Edinburg. Read for further information: https://canmore.org.uk/site/50409/cramond

.

We have to pinpoint that perhaps the most intriguing feature of Roman Cramond is located not in the castrum itself, but about a half mile further along the coastline (accessible only via a longer path which runs inland to cross the River Almond) on the Dalmeny Estate. Walking along the beach here brings you to a small outcrop of rock, in which is carved the outline of an eagle, a symbol beloved of the Romans whose legions each had their own eagle emblem behind which they marched.

The "Cramond Eagle" - if that's what it is, the carving is too weathered to say for sure - is a firm marker of the occupation of this area by the Romans, and it's quite remarkable to think about the young men who may have carved this design in between their patrols of the Antonine Wall, standing on this rocky shore and looking out over a landscape that can only have changed rudimentally in the nearly two-thousand years since.

Perhaps the carving was only a form of graffiti, the way modern cities are 'tagged' with spray paint, but nonetheless it gives a truly human shape to the Roman presence here.

The Roman fortifications in Caledonia At least 220 Roman camps have been identified throughout Scotland. 19 castrum and 7 fortlets are in the Antonine Wall.

Some of the most famous fortifications in what is now Scotland are the "Inchtuthill castrum" in the Gask Ridge area, the "Trimontium castrum" in southern Caledonia and the "Habitancum castrum/vicus" near the Hadrian Wall.

INCHTUTHIL

A string of at least four forts was built in a line from the Forth to the Tay in the AD 80s: at Camelon, Ardoch, Strageath and Bertha, just upstream from Perth. Between these forts, connected by a military road lay a series of watchtowers along an outcrop known as the Gask Ridge. A large military base was established but never fully completed at Inchuthil as the Roman headquarters for military operation in northern Caledonia.

In AD 83 the Romans are believed to have built the legionary camp of Pinnata Castra (Ptol., Geog.: ii, 3) or Victoriae (Rav. Cosm.: 108, 11) in the location that we refer to as "Inchtuthil".

This was during the Roman expansionist phase of northern Scotland and it was abandoned at around 87 AD (Pitts & St. Joseph 1985: 31, 201).The presence of a stone-wall surrounding the fort postulate the project to transform the fortress entirely in stone. Inchtuthil was the first Roman military establishment in Britannia to have defences made up of stone, derived from the northern sandstone quarry-site of Gourdie Hill.

Among the timber buildings at Inchthuthil there it is a vast structure measuring 300 x 192 feet (91 x 59 m). Its central open courtyard is surrounded by double ranges of small rooms set on either side of a corridor. This building has been identified as the legion’s hospital, or valetudinarium. The rooms off the corridor have been identified as wards, each large enough to have accommodated four beds (or eight double bunks). There appear to be about sixty of them, which suggests that one had been allocated to each of the legion’s centuries. Archaeologists have found numerous surgical instruments in the castrum. Many are remarkably similar to their modern counterparts, indicating that complex operations were routinely carried out.

The

plateau where the Inchtuthil castrum was built has

highlighted

the

presence

of

external civilian settlements, that lasted until the early subroman period. Before

the

legionaries

abandoned

southern

Scotland,

withdrawing

south

to

Hadrian’s

Wall,

they

demolished

what

they

had

built

at

Inchtuthil.

Over seven tons of handmade (nearly a million) iron nails of a considerable hardiness were buried on the site. This has been taken as an indication that they could not be transported during the withdrawal. This demonstrates the possibility -according to historian A. Montesanti (read http://www.instoria.it/home/inchtuthil.htm ) that this must have been a desperate disappointment for the Romans to have left such a resource and probably for that reason were found only 9 iron tyres (Pitts & St. Joseph 1985: 110-113).

Of course, this could mean that the Romans were planning to return to the Inchtuthil site and complete the castrum, in an area that -according to Montesanti- could have been the capital ot the possible "Caledonia provincia".

TRIMONTIUM

Trimontium castrum was created in the first century (in an area near actual Newstead) and occupied by the Romans intermittently from 80 to 211 AD. The fort was likely abandoned from c. 100-105 AD until c. 140 AD and possibly rebuilt with improvements even under emperor Septimius Severus. In the third century the castrum was abandoned, when Caracalla withdrew to the Hadrian Wall (read https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/52636/The%20Scottish%20campaigns%20of%20Septimius%20Severus%20208-211%20-%20A%20reassessment%20of%20the%20evidence.pdf?sequence=4) But the civilian "vicus" seems to have survived until Sub-roman times.

At the height of the Roman occupation of the fort, more than 1500 soldiers were living inside and a small civilian "vicus" spread around the fort to house artisans, suppliers and traders.

The principal buildings were laid out in a strict pattern within the fort: the headquarters was the ‘Principia’; nearby was the Commandant’s house and the officers’ homes – all with the luxury of under-floor heating. There were also barracks, a granary with enough grain for a year, stables and a drill hall. The workshop and baths were built outside the ramparts in case of fire. In the castrum area archaeologists have discovered a good series of coins and datable pottery.

A small amphitheater was recently discovered, with a little capacity of nearly two thousand spectators. It is the most northerly one known in the Roman empire.

in the 1980s geophysical surveys and excavations in the annexes surrounding the Trimontium castrum revealed an extensive shanty-town of timber structures set along wide streets. Some of these buildings seem to have been domestic, and perhaps housed soldiers’ families. Others may have been shops, taverns, and other places of entertainment for the troops.

Yet others show evidence of industrial or agricultural use:outside the castrum there were two areas occupied by civilians, one -to the north- with manufacturing activities. Trade with local natives took place, as demonstrated by the recovery of Roman artefacts from "Brochs" and rectilinear farmstead enclosures in the Newstead area: in other words, there was interaction between the Romans and the Caledonian tribes near Trimontium, showing a huge degree of romanization of southern Caledonia in the second century (and initial third century until Septimius Severus).

HABITANCUMHabitancum (also called "Habitantium") was a castrum created in the second century just north of the Hadrian Wall, that successively in the following decades developed an important vicus. The existence of a civilian settlement and a burial ground outside the fort is confirmed by the discovery of seven tombstones. They were set for civilians and soldiers. The settlement probably surrounded the camp in the west, east and south, but has not been explored to date.

Perhaps the carving was only a form of graffiti, the way modern cities are 'tagged' with spray paint, but nonetheless it gives a truly human shape to the Roman presence here.

The Roman fortifications in Caledonia At least 220 Roman camps have been identified throughout Scotland. 19 castrum and 7 fortlets are in the Antonine Wall.

Some of the most famous fortifications in what is now Scotland are the "Inchtuthill castrum" in the Gask Ridge area, the "Trimontium castrum" in southern Caledonia and the "Habitancum castrum/vicus" near the Hadrian Wall.

INCHTUTHIL

A string of at least four forts was built in a line from the Forth to the Tay in the AD 80s: at Camelon, Ardoch, Strageath and Bertha, just upstream from Perth. Between these forts, connected by a military road lay a series of watchtowers along an outcrop known as the Gask Ridge. A large military base was established but never fully completed at Inchuthil as the Roman headquarters for military operation in northern Caledonia.

In AD 83 the Romans are believed to have built the legionary camp of Pinnata Castra (Ptol., Geog.: ii, 3) or Victoriae (Rav. Cosm.: 108, 11) in the location that we refer to as "Inchtuthil".

Aerial photo showing the Inchuthil castrum's archeological site clearly distinguishable

|

This was during the Roman expansionist phase of northern Scotland and it was abandoned at around 87 AD (Pitts & St. Joseph 1985: 31, 201).The presence of a stone-wall surrounding the fort postulate the project to transform the fortress entirely in stone. Inchtuthil was the first Roman military establishment in Britannia to have defences made up of stone, derived from the northern sandstone quarry-site of Gourdie Hill.

Among the timber buildings at Inchthuthil there it is a vast structure measuring 300 x 192 feet (91 x 59 m). Its central open courtyard is surrounded by double ranges of small rooms set on either side of a corridor. This building has been identified as the legion’s hospital, or valetudinarium. The rooms off the corridor have been identified as wards, each large enough to have accommodated four beds (or eight double bunks). There appear to be about sixty of them, which suggests that one had been allocated to each of the legion’s centuries. Archaeologists have found numerous surgical instruments in the castrum. Many are remarkably similar to their modern counterparts, indicating that complex operations were routinely carried out.

Over seven tons of handmade (nearly a million) iron nails of a considerable hardiness were buried on the site. This has been taken as an indication that they could not be transported during the withdrawal. This demonstrates the possibility -according to historian A. Montesanti (read http://www.instoria.it/home/inchtuthil.htm ) that this must have been a desperate disappointment for the Romans to have left such a resource and probably for that reason were found only 9 iron tyres (Pitts & St. Joseph 1985: 110-113).

Of course, this could mean that the Romans were planning to return to the Inchtuthil site and complete the castrum, in an area that -according to Montesanti- could have been the capital ot the possible "Caledonia provincia".

TRIMONTIUM

Trimontium castrum was created in the first century (in an area near actual Newstead) and occupied by the Romans intermittently from 80 to 211 AD. The fort was likely abandoned from c. 100-105 AD until c. 140 AD and possibly rebuilt with improvements even under emperor Septimius Severus. In the third century the castrum was abandoned, when Caracalla withdrew to the Hadrian Wall (read https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/52636/The%20Scottish%20campaigns%20of%20Septimius%20Severus%20208-211%20-%20A%20reassessment%20of%20the%20evidence.pdf?sequence=4) But the civilian "vicus" seems to have survived until Sub-roman times.

At the height of the Roman occupation of the fort, more than 1500 soldiers were living inside and a small civilian "vicus" spread around the fort to house artisans, suppliers and traders.

|

| Bronze Roman helmet dating to 80–90 AD that was discovered at Trimontium |

The principal buildings were laid out in a strict pattern within the fort: the headquarters was the ‘Principia’; nearby was the Commandant’s house and the officers’ homes – all with the luxury of under-floor heating. There were also barracks, a granary with enough grain for a year, stables and a drill hall. The workshop and baths were built outside the ramparts in case of fire. In the castrum area archaeologists have discovered a good series of coins and datable pottery.

A small amphitheater was recently discovered, with a little capacity of nearly two thousand spectators. It is the most northerly one known in the Roman empire.

in the 1980s geophysical surveys and excavations in the annexes surrounding the Trimontium castrum revealed an extensive shanty-town of timber structures set along wide streets. Some of these buildings seem to have been domestic, and perhaps housed soldiers’ families. Others may have been shops, taverns, and other places of entertainment for the troops.

Yet others show evidence of industrial or agricultural use:outside the castrum there were two areas occupied by civilians, one -to the north- with manufacturing activities. Trade with local natives took place, as demonstrated by the recovery of Roman artefacts from "Brochs" and rectilinear farmstead enclosures in the Newstead area: in other words, there was interaction between the Romans and the Caledonian tribes near Trimontium, showing a huge degree of romanization of southern Caledonia in the second century (and initial third century until Septimius Severus).

Trimontium was extensively excavated

in the early years of the twentieth century, producing an outstanding collection

of Roman artefacts, from humble wooden tent pegs to highly decorated military

parade helmets (see photo above), all now in the National Museums of Scotland.

Even when abandoned by their builders, the Roman ruins at Newstead seem to have retained some kind of significance. That the area was inhabited in post-Roman times is proved by the occurrence of Roman dressed stones in an earth-house (RCAHMS 1956, No.611). Read for further information: https://canmore.org.uk/site/55620/newstead.HABITANCUMHabitancum (also called "Habitantium") was a castrum created in the second century just north of the Hadrian Wall, that successively in the following decades developed an important vicus. The existence of a civilian settlement and a burial ground outside the fort is confirmed by the discovery of seven tombstones. They were set for civilians and soldiers. The settlement probably surrounded the camp in the west, east and south, but has not been explored to date.

|

| The only remains of the walls in the "Habitancum" castrum |

The Antonine Fort from AD 139 was probably built for the second invasion of Scotland, but was destroyed in 197AD. Severan Fort built on the same site, but differently alined about 205/208 AD. The rebuilding of the fort would have been part of a major refurbishing of the Wall undertaken in the first years of the third century.

The visible remains at Habitancum are of a fort constructed in the early years of the third century AD by the Emperor Severus; an inscribed slab, uncovered by excavation, records the construction of the fort by a 1000 strong mounted cohort (one of the ten units of a Roman legion). The walls of the fort are substantial features up to 10m wide and standing to a height of 0.5 to 1.2m above the interior of the fort.The remains of the internal Roman buildings are thought to lie beneath this later settlement; partial excavations in the 1840s revealed the layout of the bath house situated in the south east angle of the fort and a headquarters building situated at the centre of the fort.

Excavations also uncovered early second century pottery and evidence of burning beneath the present western rampart; this has been taken to suggest that the present visible remains resulted from the reconstruction of an earlier 2nd century fort built under the Emperor Antoninus Pius and probably destroyed during the invasions of northern tribes recorded in the late second century AD. Some historians think that Habitancum was historically very important because it was the capital of the "Valentia provincia", created by Count Theodosius in the fourth century and populated by romanised Britons with some Roman citizens. The fort is believed to have been definitively destroyed around 397 AD, but the vicus remained inhabited until the first decades (and probably beyond) of the Sub-Roman period in the fifth century.

_p%C3%A5_tre_sidor..jpg)