Battle of Gela and the Livorno Division

The Division Livorno was one of the best Italian Divisions during WW2 and was going to be used in the conquest of Malta in 1942, together with another famous unit: the Folgore Division. The Livorno under the command of general Domenico Chirieleison was transferred to central Italy in spring 1942. Here she was intensively trained as an amphibious maneuvering unit for landing in Malta (later not implemented) and was then led by Chirieleison to Sicily. At the time of the Allied invasion of the island, on 10 July 1943 it was immediately used as a maneuvering unit.

Stationed in the area of Gela, the landing place of the 1st US Infantry Division, on the morning of July 11, the Livorno Division carried out an important counterattack in that sector, which was only crushed by the naval battery consisting mainly of American cruisers USS Boise and Savannah armed with 15 cannons 152/47 mm each, which caused considerable losses among the Livorno soldiers (about 7 000 fallen, wounded and missing men).

Stationed in the area of Gela, the landing place of the 1st US Infantry Division, on the morning of July 11, the Livorno Division carried out an important counterattack in that sector, which was only crushed by the naval battery consisting mainly of American cruisers USS Boise and Savannah armed with 15 cannons 152/47 mm each, which caused considerable losses among the Livorno soldiers (about 7 000 fallen, wounded and missing men).

The "Battle of Gela" happened for nearly 4 days from July 10, 1943 when the Allies landed in southeastern Sicily just in front of the small city of Gela. In those few days of heavy fighting died and/or were wounded 7200 Italians, 560 Germans and more than 6000 Americans (please see video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZgUTj46Zc8A ).

Soon after the landing the Italian Division "Livorno" started a counterattack that was nearly successful in throwing back the invaders in the Gela beach. A group of Italian tanks entered a few hours after the landings inside Gela and were stopped at a few hundred meters from the city's beach.

The beaches around Gela were defended by the Italian XVIII Coastal Brigade, the town itself was defended by the Italian 429th Coastal Battalion while the Italian 4th Mountain Infantry Division Livorno, an elite battalion composed by high quality troops with sufficient transports to move all of its infantry units simultaneously, was positioned near Niscemi and supported by the Italian "Mobile Group E" at Ponte Olivo with 38 Fiat 3000 (and some Renault R 35) tanks to respond when invasion points became known. They were considered by the Germans and most Italians to be far superior to the other divisions, as they had originally been intended for the assault on Malta in June, 1942.

They were joined on the afternoon of the first day by the German Fallschirm-Panzer Division 1 Hermann Göring with 46 Panzerkampfwagen III and 32 Panzerkampfwagen IV tanks from Caltagirone, reinforced with a regiment of the 15th Panzergrenadiers with the 215th Panzer Battalion attached with 17 Tiger I tanks.

The Livorno Division fought bravery trough all the duration of the conflict. These soldiers carried out a substantial counterattack on 10-11 July, 1943, and threatened to “throw the invaders back into the sea”, being stopped just few hundred meters from the beaches. On 10 July Livorno infantry supported by the 155th Bersaglieri Motorcycle Company and a column of tanks poured onto Highways 115 and 117 and nearly took back the city of Gela, but guns from the destroyer Shubrick and the light cruiser Boise destroyed several Fiat 3000 tanks (a L.5/30 variant) and Re. R 35 light tanks. Also, Allied forces has attacked a division right flank from Licata in the direction of Ravanusa and Riesi, tying up much of Italian troops.

The Amphibious Battle of Gela was reported by an American newspaper: “Supported by no less than forty-five tanks, a considerable force of infantry of the Livorno Division attacked the American troops around Gela. The American division beat them back with severe casualties. This was the heaviest response to the Allied advance.”

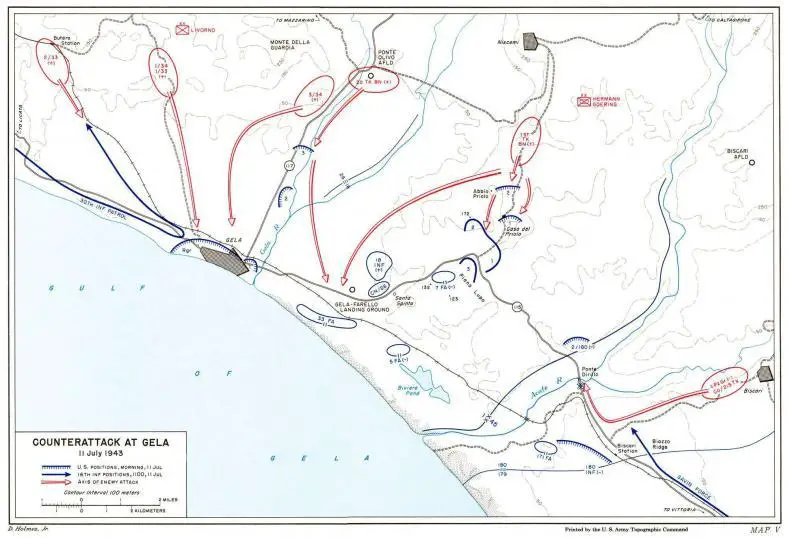

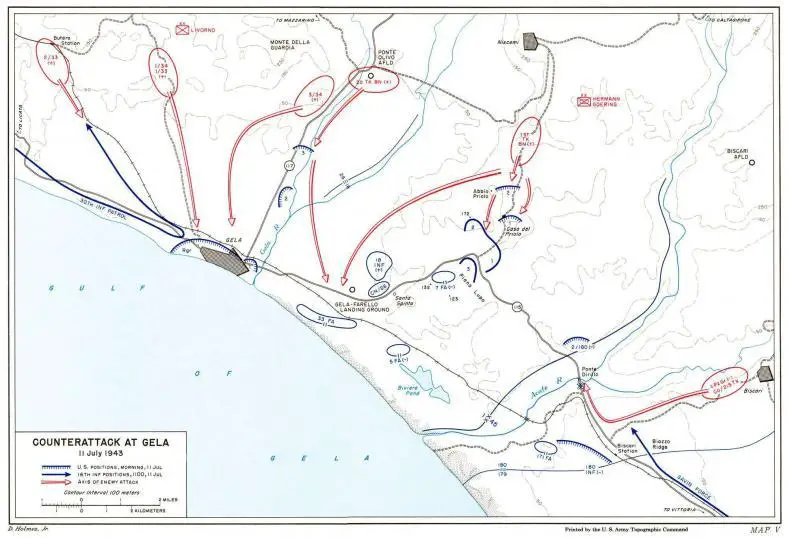

Map of the initial Battle on July 10 (according to the US Army official documents)

Soon after the landing the Italian Division "Livorno" started a counterattack that was nearly successful in throwing back the invaders in the Gela beach. A group of Italian tanks entered a few hours after the landings inside Gela and were stopped at a few hundred meters from the city's beach.

The beaches around Gela were defended by the Italian XVIII Coastal Brigade, the town itself was defended by the Italian 429th Coastal Battalion while the Italian 4th Mountain Infantry Division Livorno, an elite battalion composed by high quality troops with sufficient transports to move all of its infantry units simultaneously, was positioned near Niscemi and supported by the Italian "Mobile Group E" at Ponte Olivo with 38 Fiat 3000 (and some Renault R 35) tanks to respond when invasion points became known. They were considered by the Germans and most Italians to be far superior to the other divisions, as they had originally been intended for the assault on Malta in June, 1942.

They were joined on the afternoon of the first day by the German Fallschirm-Panzer Division 1 Hermann Göring with 46 Panzerkampfwagen III and 32 Panzerkampfwagen IV tanks from Caltagirone, reinforced with a regiment of the 15th Panzergrenadiers with the 215th Panzer Battalion attached with 17 Tiger I tanks.

The Livorno Division fought bravery trough all the duration of the conflict. These soldiers carried out a substantial counterattack on 10-11 July, 1943, and threatened to “throw the invaders back into the sea”, being stopped just few hundred meters from the beaches. On 10 July Livorno infantry supported by the 155th Bersaglieri Motorcycle Company and a column of tanks poured onto Highways 115 and 117 and nearly took back the city of Gela, but guns from the destroyer Shubrick and the light cruiser Boise destroyed several Fiat 3000 tanks (a L.5/30 variant) and Re. R 35 light tanks. Also, Allied forces has attacked a division right flank from Licata in the direction of Ravanusa and Riesi, tying up much of Italian troops.

The Amphibious Battle of Gela was reported by an American newspaper: “Supported by no less than forty-five tanks, a considerable force of infantry of the Livorno Division attacked the American troops around Gela. The American division beat them back with severe casualties. This was the heaviest response to the Allied advance.”

Map of the initial Battle on July 10 (according to the US Army official documents)

The Livorno regrouped and made a further attempt to take Gela back one day later and the 3rd Battalion, 34 Livorno Regiment, is recorded by its Commanding Officer as having made a valiant effort in the Gela Beachhead.

But on 15 July, 1943, the Allied armoured units had attacked from west between Valguarnera Caropepe and Raddusa, threatening to encircle the Livorno division. Raddusa was lost by Italians on July 18, 1943 after heavy fighting, and the Livorno division has taken a stand at Simeto river down to the river mouth south of Catania. On July 22, 1943 the Livorno division was subject to heavy coastal bombardment by British ships between Leonforte and the Simeto river mouth, but managed to hold positions. Failures of other Axis units in Sicily then forced a Livorno division to retreat north.

At Casa del Priolo, halfway between Piano Lupo and Niscemi, where less than 100 men of the 1st Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry, had, under Lt. Col. Arthur Gorham, reduced a strongpoint and set up a blocking position, an American soldier saw a column of Italian tanks and infantry heading his way. Alerted, the paratroopers allowed the point of the column, three small vehicles, to enter their lines before opening fire, killing or capturing the occupants. The sound of firing halted the main body. After thirty minutes of hesitation, about two infantry companies shook themselves out into an extended formation and began moving toward the Americans, who waited until the Italians were 200 yards away. Then they opened a withering fire not only of rifles but of the numerous machine guns they had captured when they had taken the strongpoint. Their first fusillade pinned down the enemy troops except for a few in the rear who managed to get back to the main column.

Several minutes later, the Italians moved a mobile artillery piece into firing position on a hill just out of range of any weapon the paratroopers possessed. As the gun opened fire, a previously dispatched paratrooper patrol returned and reported to Colonel Gorham that there appeared to be no strong enemy force at the battalion's original objective. This was the road junction on Piano Lupo, where only a few Italians armed with machine guns held a dug-in position surrounded by barbed wire. Unable to counter the artillery fire, Gorham decided to make for Piano Lupo. The move would have several advantages: it would put him on his objective and closer to the 16th RCT, which he was supposed to contact; it would probably facilitate contact with other paratroopers. Even though naval gunfire began to come in on the Italian column, Gorham had no way of controlling or directing the fire. Leaving one squad to cover the withdrawal, he started the paratroopers south, staying well east of the Niscemi-Piano Lupo road to escape the effects of the naval fire. It was then close to 0930.10

The naval gunfire had come in response to a call from observers with the 16th RCT's leading battalions, which were moving toward Piano Lupo. Because the RCT's direct support artillery unit, the 7th Field Artillery Battalion, was not yet in firing position, the destroyer Jeffers answered the call with nineteen salvos from her 5-inch guns.11 A few of the Italian tanks were hit, but the majority were unscathed. No Italian infantry ventured past the Piano Lupo road junction, for they preferred to take cover from the relatively flat trajectory naval fire in previously prepared defensive positions. Masked on the south by high ground that caused most of the naval fire to overshoot the junction, the Italian infantrymen reached and occupied their positions just a few minutes ahead of Gorham's paratroopers.

The Italian tanks that passed through the fire, about twenty, continued past the road junction and turned on Highway 115 toward Gela. They proceeded downhill only a short way. The two forward battalions of the 16th RCT, though armed only with standard infantry weapons, knocked out two of the tanks, thoroughly disrupted the Italian thrust, and halted the column. Without infantry support, its artillery under heavy counterbattery fire from American warships, the Italian tankers broke off the fight and retired north into the foothills bordering the Gela plain on the east.

Photo of one of the Italian tanks destroyed inside Gela. The 16th RCT reported twenty tanks in this attack. (1st Inf Div G-3 Jnl, entry 17, 10 Jul 43.) The exact number of tanks in this group is not known. One report indicates Mobile Group E had nearly fifty tanks when it started its movement on 10 July (Morison, Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, p. 103). Another report (MS #R-125 (Bauer)) indicates that the Italian unit had one company (twelve to fourteen) of Renault 35 tanks; possibly sixteen 3-ton tanks; and possibly some Fiat "3,000" tanks. The Renault tanks, captured from the French in 1940, weighed two tons and were armed with 37-mm. guns. From reports contained in other American sources, the number of Italian tanks appears to have been between thirty and forty total in both Italian groups.

The threat dispersed, the 16th RCT resumed its movement to the Piano Lupo road junction. But Gorham's paratroopers, approaching from the opposite direction, arrived first. After reducing one Italian strongpoint, the paratroopers made contact with scouts from the 16th RCT at 1100.15 The 1st Battalion, 16th Infantry (Lt. Col. Charles L. Denholm), then cleaned out several remaining Italian positions around the road junction, a task facilitated by a captured map, while the 2d Battalion (Lt. Col. Joseph Crawford) and the paratroopers moved across the road and occupied high ground to the northwest.

Meanwhile the heterogeneous Ranger-engineer force in Gela had observed a column of thirteen Italian tanks escorted by infantry moving south along Highway 117 toward the city--the right arm of Mobile Group E's two-pronged attack. Another column, the Livorno Division's battalion of infantry, could also be seen moving toward Gela along the Butera road. While the destroyer Shubrick started firing at the tank-infantry column on Highway 117, the Ranger-manned Italian 77-mm. guns opened up on the Livorno battalion.

The first Shubrick salvos halted the Italians in some confusion. But the tankers recovered a measure of composure; they resumed their movement, though fewer now, for several tanks were burning in the fields along the highway. Without further loss, nine or ten tanks dashed down the highway and into the city. But the same thing happened here that had happened on the Niscemi-Piano Lupo road--Italian infantrymen did not follow the tanks. And so, in the city, the Rangers and the engineers began a deadly game of hide and seek with the Italian tanks, dodging in and out of buildings, throwing hand grenades and firing rocket launchers. Colonel Darby jumped in a jeep, dashed down to the beach, commandeered a 37-mm. antitank gun, returned with it to the city and knocked out a tank. Another burned as Rangers and engineers teamed up, first to stop it and then to destroy it. After twenty minutes of this kind of fighting, the Italians started back out of the city hotly pursued by American fire. The Italian crews suffered heavily. Almost every survivor carried with him some kind of wound.

As for the Livorno Division's battalion--in almost formal, parade ground formation, the Italian infantrymen advanced against the western side of Gela. The two Ranger companies firing their captured Italian artillery pieces took heavy toll among the closely bunched enemy soldiers. Rifles, machine guns, and mortars joined in as the range closed. Not an enemy soldier reached the inner city, only the outskirts. Leaving behind numerous dead and wounded, the remnants of the Italian battalion stopped their advance.

Meanwhile the Rangers repelled an attack by a battalion of Italian infantry (an element of the 4th Livorno Division) advancing from the direction of Butera. The enemy soldiers were approaching across open ground in an unusual close-order formation, fully exposed to the American gunners. It was a baffling move by the Italians, who seemed to have a death wish. Every weapon at the Americans’ disposal-captured field guns, the 83rd’s mortars and offshore naval gunnery-rained devastation upon the hapless Italians. As a result, not one enemy soldier reached Gela.

The Italian thrust against Gela stopped, the 26th Combat Team moved from the Gela-Farello landing ground into Gela and made contact with Darby's force by noon. Two battalions swept past the city on the east, cut Highway 117, and took high ground two miles to the north. With the city firmly in American hands, Colonel Bowen, the 26th RCT commander, began to think of seizing the terrain overlooking Ponte Olivo airfield from the west. Yet he was not anxious to start until he had adequate field artillery and armor support. As of noon, Bowen had neither. Nor was the situation along the Piano Lupo-Niscemi axis clear. South of Niscemi, the right column of Conrath's two-pronged counterattack, the tank-heavy force, closed into its assembly area. The infantry-heavy force closed in the Biscari area. With all in readiness at 1400, five hours late, Conrath sent his Hermann Goering Division into its attack.

The second attack coordinated with the Germans on July 11 (according to the US Army official documents)

Conrath, the "Hermann Goerin Division" commander, who had received a call from the XVI Corps commander, went to the corps headquarters at Piazza Armerina. He learned for the first time of his attachment to the corps and together with Generale di Divisione Domenico Chirieleison, the Livorno Division commander, also in attendance, he received word of Guzzoni's plan for a co-ordinated attack against Gela. According to the plan, the attack, starting at 0600, would have the German division converging on Gela from the northeast in three columns, the Italian division converging on Gela from the northwest, also in three columns.

Northwest of Gela, General Chirieleison commander of the ''Livorno Division" ordered one column to strike at Gela from the north, a second to advance astride the Gela-Butera road and strike Gela from the northwest, the third, while guarding the division right flank against American forces near Licata, to move southeast from Butera Station to Gela. The remnants of the Italian "Mobile Group E" were to support the first column.

General Conrath at 0615, 11 July, sent the three task forces of the Hermann Goering Division forward. (Map V) At the same time, one Italian task force, the one nearest Highway 117, jumped off, but on its own initiative, apparently after seeing the German tank battalion start south from Ponte Olivo airfield. To help support the converging attacks on Gela, German and Italian aircraft struck the beaches and the naval vessels lying offshore. The 3d Battalion, 26th Infantry, which had been advancing up the east side of Highway 117, bore the brunt of the German attack. Company K was driven to the south and west toward Gela, but the remainder of the battalion held firm. The Italian column passed the 26th Infantry, bumped into Company K, which was trying to get back to Gela, and headed directly for the city. Colonel Darby's force in Gela laid down heavy fire on the approaching enemy. The 33d Field Artillery Battalion began pounding away at both columns. The two batteries from the 5th Field Artillery Battalion joined in. The 26th Infantry's Cannon Company and the 4.2-inch mortars in Gela also opened fire. The combination of fires stopped the Italians.

The bulk of the Livorno Division had by this time joined the Hermann Goering Division attack. General Conrath's two tank battalions were once again united, and though he still contended with the 16th Infantry on Piano Lupo, he decided to send the bulk of his armored force across the Gela plain to the beaches. General Chirieleison, the Livorno Division commander, was also pushing for a concentrated attack that would surge over the American positions. He had already lost one hour waiting for contact with the German unit. He did have one column engaging the Americans in Gela. Now he sent a second from Butera toward the city.

With most of the Rangers and engineers heavily engaged against the Italian thrust down Highway 117, only two Ranger companies on the west side of Gela stood in the way of Chirieleison's second column. "You will fight with the troops and supporting weapons you have at this time," Colonel Darby told them. "The units in the eastern sector are all engaged in stopping a tank attack." When the Italian column came within range, the two Ranger companies opened fire with their captured Italian artillery pieces, and with their supporting platoon of 4.2-inch mortars. The Italian movement slowed. General Patton appeared at the Ranger command post in this sector, a two-story building, and watched the Italian attack. As he turned to leave, he called out to Captain Lyle, who commanded the Rangers there, "Kill every one of the goddam bastards."

Lyle called on the cruiser Savannah to help, and before long almost 500 devastating rounds of 6-inch shells struck the Italian column. Through the dust and smoke, Italians could be seen staggering as if dazed. Casualties were heavy. The attack stalled. Moving out to finish the task, the Ranger companies captured almost 400 enemy troops. "There were human bodies hanging from the trees," Lyle noted, "and some blown to bits." As it turned out, a large proportion of the officers and more than 50 percent of the Italian soldiers were killed or wounded.

East of Gela, as General Conrath sent the major part of both his tank battalions toward the beaches, the Gela plain became a raging inferno of exploding shells, smoke, and fire. The lead tanks reached the highway west of Santa Spina, two thousand yards from the water. As they raked supply dumps and landing craft with fire, the division headquarters reported victory: "pressure by the Hermann Goering Division & Livorno Division [has] forced the enemy to re-embark temporarily." At Sixth Army headquarters, General Guzzoni was elated. After discussion with General von Senger, he instructed XVI Corps to put the revised plan into action: wheel the German division that afternoon to the east toward Vittoria.

General Faldella, the Sixth Army chief of staff, reported (Lo sbarco, page 148) an intercepted Seventh Army radio message that ordered the U.S. 1st Division to prepare for re-embarkation. Faldella repeated this to Mrs. Magna Bauer in Rome during an interview in January 1959, asking repeatedly whether the original message appeared in the official records (that "strangely" disappeared after WWII)

At 11.00 the Americans retreated inside Gela and Italian troops reached the railway station, while the German tanks reached the beaches south of Gela. The Americans were desperate and started to fear their beachhead lost. Exactly at that hour the headquarters of the VI Italian Army obtained an encrypted message from general Patton ordering to get ready for possible return to ships. But suddenly tanks and troops commanded by colonel Galvin from the south hit the Germans and forced them to stop the winning offensive. The German tanks were hard hit by the navy guns and started to retreat in the early afternoon with heavy losses.

But the German tanks never reached the 1st Division beaches. Nor was there any hint of American re-embarkation. The 32d Field Artillery Battalion, coming ashore in Dukws moved directly into firing positions along the edge of the sand dunes and opened direct fire on the mass of German armor to its front. The 16th Infantry Cannon Company, having just been ferried across the Acate River, rushed up to the dune line, took positions, and opened fire. Four of the ten medium tanks of Colonel White's CCB finally got off the soft beach, and, under White's direction, opened fire from the eastern edge of the plain. The 18th Infantry and the 41st Armored Infantry near the Gela-Farello landing ground prepared to add their fires. Engineer shore parties stopped unloading and established a firing line along the dunes. Naval gunfire, for a change, was silent--the opposing forces were too close together for the naval guns to be used.

Under the fearful pounding, the German attack came to a halt. Milling around in confusion, the lead tanks were unable to cross the coastal highway. The German tanks pulled back, slowly at first and then increasing their speed as naval guns opened fire and chased them. Sixteen German tanks lay burning on the Gela plain.

North of Gela, artillery and naval fire, small arms, machine gun, and mortar fires reduced the Livorno column to company size, and these troops were barely holding on to positions they had quickly dug. The third Italian column, in about battalion size, starting to move from Butera Station to Gela, ran into a combat patrol which had been dispatched by the 3d Division to make contact with the Gela force. The company-size patrol inflicted heavy casualties on the Italians, who pulled back to their original position.

The battering received during this attack on Gela finished the Livorno Division as an effective combat unit.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The following are excerpts from Lt. Col. Dante Ugo Leonardi (formerly commander of the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment of the Livorno Division) book entitled "Luglio 1943 in Sicilia" (July 1943 in Sicily). Indeed it provides an Italian account, written by the unit’s commanding officer himself, as one of the bloodiest actions carried out by an Italian infantry unit in WWII. Modern Italy does not even bother to devote to those unsung heroes a tenuous, fleeting thought. May this tiny contribution stands as a memorial:

3rd Battalion, 34th Regiment, “Livorno” Infantry Division in the Gela Beachhead Counterattack: Sicily, July 11th-12th, 1943

Marching to Battle

3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment (commander: Col. C. Martini), led by Lt. Col. D. U. Leonardi, was attached to the “Livorno Infantry Division”, which was deployed in Sicily in November 1942. The Division was at nearly full strength; the artillery, engineers and 4 out of 6 infantry battalions were fully motorized (rarities, in the wartime Italian Army). It was the best Italian Division in Sicily, as it had been picked out and trained for the eventually evaporated Malta amphibious/airborne invasion.

Unlike most other Italian units in Sicily, the Division’s morale was relatively high and most officers’ leadership quality was good. However, the insufficient training plagued “Livorno” as well as the vast majority of Italian Army outfits at all levels, and sorely reduced its effectiveness in combat.

The Division’s troops were green. They had never been tested in combat.

When the Allied invasion of Sicily was launched, 3rd Battalion’s strength was 34 officers, 1100 NCOs, and enlisted men, (4) 47/32 mm guns, (6) 81 mm mortars, 12 machine guns and a flamethrower squad. It had taken up quarters in the Caltanissetta-Belvedere-San Cataldo area, in the central-southern region of the island.

At 00:30 am, July 10th, 1943, a regimental dispatch-rider arrived at the Battalion’s quarters carrying a written order. “Be this Battalion alarmed and ready for a possible action. Further instructions will follow.” At 5:00 pm on the same day, the movement order was delivered to the Battalion:

Enemy landed at Gela in the July 9th/10th night. Despite local defense reaction, enemy managed to establish a bridgehead. More landings ongoing in various southeastern coast localities. Enemy air activity much intense, especially along communication lines and over towns. This Battalion at 7:00 pm hours today, will initiate movement on vehicles towards Ponte Olivo (Gela Plain). Once arrived there, it will stop, waiting for further orders. ……1st Group [Battalion], 28th Artillery Regiment, specifically allotted to this Battalion for fire support. Direct agreement.

At exactly 7:00 pm the unit, in battle order, got on the trucks and vehicles and set off towards the assigned locality. The baggage (commander, Lt. S. Rossi) was left at the San Cataldo quarters: on the following day, it was destroyed by a heavy air raid, and the civilian population plundered all the surviving goods and materials.

Before dusk, an enemy aircraft formation strafed the traveling column. The attack caused limited damage (2 dead, 20 wounded, 5 vehicles damaged). It was the Battalion’s baptism of fire.

In the darkness of the night, the column stopped in the town of Mazzarino and the officers asked a Carabinieri (military police) patrol about the right way to Gela. There were some groups of civilians, silent and cold. They looked by no means enthusiastic towards their own troops, as Leonardi later recalled.

At the Butera-Gela road fork, Leonardi received a written instruction coming from the Regiment commander:

You will attack the Americans in the early hours of tomorrow July 11th, towards Gela. Deploy the Battalion, under the cover of darkness, between Ponte Olivo and Mount Castelluccio.Regiment Commander

Leonardi was quite surprised by the generic, insufficient information conveyed by the message. Where precisely was the enemy? Where was the beachhead’s front? How strong was the enemy? Where were their forward lines, and where were ours?

At 11:00 pm, the column reached Ponte Olivo. The place looked deserted and nobody was around, except for a few soldiers guarding a bridge, who didn’t even know the whereabouts of the nearest Italian units! No further information!

The troops dismounted and the whole Battalion headed south, by foot, wandering across the fields, literally seeking the first enemy line. After a few kilometers, the rambling Battalion came across an anti-tank unit in position astride Highway 117, the main road leading to Gela, but its commander had just arrived there, too, and did not know anything about the situation. Lack of information and disorganization were rampant that night. However, the antitank unit officer pointed to a nearby artillery battery. Perhaps they would have a clearer idea about the situation. The battery commander, a Lieutenant, finally accompanied the Battalion’s officers to Mount Castelluccio (Castle Hill).

Up there, they found the 155th Bersaglieri Motorcycle Company, led by Lt. Franco Girasoli, wounded in action during the July 10th attack on the beachhead. His company, belonging to the Mobile Group E, had suffered heavily, and the remnants were holding the hill. It was the only Italian infantry unit left in the area prior to the 3rd Battalion’s arrival. Girasoli was a capable and valiant officer and his elevated fighting spirit impressed Leonardi.

The Preparation

Behind Mount Castelluccio there is a wide depression, seeming almost perfect as a safe deployment area for the Battalion; the men would have been sheltered from the enemy line of sight, and partly from enemy fire. However, very little information was available about the foe that the Battalion would have faced on the next day. It was American infantry, dug in along a row of hills not far away from Mount Castelluccio and south of it.

At dawn, the Battalion was ready for action. Units, weapons, the ammunition supply post had all been arranged and prepared the best possible way. No traces yet of the Artillery Group which would have supported the Battalion’s attack. According to the previous day’s orders, a Battalion’s company, (the 11th), was positioned quite far away from the other troops. This was partly due to a bad understanding of the orders issued and deployment errors caused by night movement across unknown areas. This would have had brought about several drawbacks and worries during the subsequent actions.

The Battalion’s officers, while awaiting the attack order, inspected the terrain in which their troops would soon have crossed under fire. The nearest enemy elements were located on some hills around 800 meters south of Mount Castelluccio. Overhanging the flat terrain and completely bare, stretching between Castelluccio and the hills themselves, was devoid of vegetation (corn had been reaped just a few days before), and nearly featureless aside from a few shallow ditches here and there. The troops would have been fully exposed to automatic weapons fire for the whole duration of the action.

Axis aircraft bombing Allied ships at Gela.

Lying on a hilltop, on the southern horizon, the town of Gela, nearly 4 kilometers away was visible, inviting and alluring. Farther south, the blue sea… powdered with countless Allied ships. It was a majestic sight.

The Plan

A Captain, quickly came from the Division HQ and delivered the attack order.

Three strike columns would have simultaneously assaulted the beachhead, starting at 6:00 am, after 10 minutes of artillery barrage fire. Objective: Gela. The right column was the 33rd Infantry Regiment of the “Livorno” Division. The left column was the German “Hermann Goering” Division. The center column was the 3rd Battalion, 34th Inf. Regt.

It was immediately obvious that while the main effort had to be exerted by the far stronger right and left columns, the 3rd Battalion would just have supported their drive by pinning down the Americans in front of it and pushing them back as the other two pincers progressed toward Gela.

The Battalion had no radio gear to get in touch with the other attack forces, and low hills separated it from the neighboring columns and even forbade visual contact. Thus each strike force was separated from the others and, as it turned out during the fighting, the counterattack was marred by the utter lack of both coordination efforts as well as American firepower.

Even worse, while the two main prongs of the attack were being stopped, badly mauled and driven back, the 3rd Battalion, without any knowledge of what was going on elsewhere, still kept on moving forward, eventually finding itself exhausted and stuck in the outskirts of Gela – alone and isolated.

Infantry reinforcements were promised – however, they never arrived.

The Onrush

The Battalion was set up in assault array:

9th Company (Capt. Capello), forward left

10th Company (Capt. Ferrara), forward right

11th Company (Lt. Florio), behind the 10th

12th (Heavy Weapons) Company (Lt. La Torre): 47/32 mm guns with the forward infantry companies; flamethrower squad with 9th Coy; 81 mm mortars on Mount Castelluccio;

10th Company (Capt. Ferrara), forward right

11th Company (Lt. Florio), behind the 10th

12th (Heavy Weapons) Company (Lt. La Torre): 47/32 mm guns with the forward infantry companies; flamethrower squad with 9th Coy; 81 mm mortars on Mount Castelluccio;

HQ Company

At 5:50 am, just when the supporting artillery should have opened fire, the I/28th Artillery Group was not ready to accomplish its fire mission yet. Major E. Artigiani, the Group commander, had reached Mt. Castelluccio just a half an hour before. Artigiani, inside a shell crater, was striving to establish a radio connection with his gunners. The guns were also arriving from the San Cataldo area and had to be set up 2 kilometers north of the infantry forward line.

The attack was delayed until 6:30 am to allow time for the artillery to get ready, but when the order was issued, the guns didn’t fire – they entered the fray later when the attack had already been launched. The delay seemed to last forever and the Battalion’s officers grew nervous with the tough situation. It was a three-pronged coordinated and simultaneous attack on a broad front to be executed by three separated strike forces. A further delay might cause very heavy consequences leading to an unqualified fiasco. On the other hand, attacking a superior enemy without artillery support meant running even greater risks with the troops possibly undergoing harsher punishment. Leonardi notes: “Under such circumstances, all that we can do is to trust the goodness of God”.

3rd Battalion, 34th Regiment Livorno begins the assault towards Gela.

At 6:30 am, the troops, with the officers ahead of their men, leaped out and surged forward towards the enemy. As soon as the attack started, American guns and mortars opened a massive suppression fire on the attackers. Casualties began to mount up. Capt. D. Capello, 9th Company commander, was wounded twice very soon. 30 meters away from the Battalion commander, who was with 10th Company, a shell splinter lopped off a soldier’s head.

The Battalion’s heavy weapons, light guns, and mortars delivered blow after blow to the enemy positions, and this somehow helped to counterbalance the American fire, whose volume increased as the Italians got nearer. Eight American infantrymen with 2 machine guns were inside a small house on the battlefield; their accurate fire was a serious hindrance to the Italian advance. Lt. La Torre, with a handful of riflemen, attacked the outpost with hand grenades. The Americans were captured. Sergeants E. Caponi and Q. Ghioni, 9th Company, proved their valor in the face of death, Ghioni being wounded twice, but going on leading his squad to seize an enemy automatic weapons post. He was eventually killed.

At around 8:00 am, the Battalion reached its first objective line. The US infantry encountered [probably, Company K, 3rd Battalion, 26th Infantry Regiment] was not solidly entrenched and made no further attempts to stand; it swiftly fell back, leaving several prisoners and weapons in Italian hands.

Italian losses had been quite heavy, but that was only the beginning. For along another chain of low hills, 500 meters south of the just seized position, a more solid and better organized American defense line [Darby’s force] greeted the already worn out Italians with a withering fire. The worst was still to come.

The Slaughter

The much longed for artillery support, at last, thundered overhead and the first shells hit the U.S line. It was a morale boost for the green infantrymen, who had seen so many numerous comrades fall in their very first war action.

But it was a short-lived illusion. Hell broke loose as US naval gunfire added its weight to the field artillery and the heavy mortars and beat the battlefield like a carpet, hammering away at the unarmored infantrymen with huge violence.

The Battalion resumed the attack but the enemy reaction proved very tough this time, and movement was considerably slowed down while casualties became rapidly staggering. It took the companies 3 hours to cover 500 meters. Shells, splinters, and bullets zinging and sweeping across in the thousands and exploding everywhere on the flat ground were simply slaughtering the men. It was a cataclysmic scenario and the uproar of landing shells, deafening. Yet the troops did not give up and persisted to advance. (Infantry elements of the German Hermann Goering Division, being as badly battered as the 3rd Battalion, broke and ran).

Unfortunately, the pitiful training of the Italian infantry made things even worse. Instead of scattering across the field to increase the very few survival chances in the high explosive storm, many men formed packed groups, seeking refuge in the comrades’ presence. Obviously, this automatic reflex was paid for with more human lives mowed down.

Finally, 9th Company communicated to the Battalion HQ that due to the bloody losses suffered and the relentless American fire, it was unable to further move. All company officers had been killed or wounded.

Italian soldiers on the receiving end of U.S. naval gunfire near Gela.

In the meantime, 10th Company was being cut to pieces. It had managed to get very near the U.S posts, but by now it was being hit frontally by a torrent of bullets, enfiladed from the left, and smashed by naval gunfire and mortars. The company commander, Capt. Ferrara, was heavily wounded and two out of three platoon commanders were killed.

An American machine gun selected as its target the Battalion HQ. The HQ personnel found a meager cover in a shallow ditch, but they were pinned down and couldn’t move. Sergeant E. Benassi, lying in a ground hole, managed to take up a Breda submachine gun and a deadly duel began. Sgt. Benassi stood very slim chances of making it against the MG and everybody expected to see him die very soon. But a prolonged burst of the Breda silenced the MG a few minutes later.

The Battalion was thus stuck on the open ground and being quickly chewed up by a hail of lead and steel which no other troops in the world could have withstood for a longer time. Losses were horrendous and the breaking point was near.

That very moment, however, the reserve company, the 11th, sprang forward and hit the American elements, enfilading 10th Company, while the remnants of 9th and 10th Company joined the assault getting within hand-to-hand combat distance.

The enemy avoided the infantry shock by disengaging and withdrawing. More prisoners and abandoned equipment were seized.

The fighting petered out. At 11:00 am, the battalion seized the American line and fire ceased.

Leonardi inspected what was left of his exhausted unit. 10th Company had been reduced to 30 men and no officers; they formed a platoon under Lt. Petrillo. The other companies were not in much better shape. 9th Company’s strength became halved.

Lt. Baldassare, commander of the recon platoon, was ordered to go on patrol duty and observe the enemy’s moves. Later during the day, he sent the following message back to the Commander: “No traces of Americans in the area we patrolled. They are still falling back into Gela. Patrol stands near the Gela roadblock. Waiting for orders.”

It was clear that the Americans had retreated into the town of Gela. Fighting inside the town in those conditions was out of the question; a folly, which would have destroyed the Battalion to the last man. Nothing was known, moreover, about the outcome of the other two prongs’ attacks.

Nevertheless, Leonardi thought it expedient to take advantage of the lull by pushing forward at least on the outskirts of the town, to the Gela roadblock.

While the troops were progressing, the Regiment commander, Col. C. Martini, sent an encouraging, cheerful message, praising the Battalion for its “superb behavior in battle” and “the brilliant result attained”.

Just when the companies had reached the Gela roadblock position and were digging in, naval gunfire suddenly hit them murderously. Major Artigiani died and several officers and soldiers wounded, including Lt. Baldassare and Lt. Mascellani, platoon leader of the 11th Company.

Italian mortar action against American forces at Gela.

Leonardi wrote an abridged report to Col. Martini, pointing out the heavy losses suffered (only 400 men remained) and the critical conditions of the unit, as well as the utter impossibility to go farther. Urgent requests came for ammunition, fuel for the supply vehicles (mostly “motor tricycles”), and reinforcements. The Regiment commander replied that he had already requested reinforcements and they should have been on the way; the Battalion had to consolidate its gains, guard the conquered position and repel any attacks until the arrival of the reinforcements.

In the afternoon, some reinforcements arrived. Not the infantry battalion expected, but the 3rd (divisional) mortar company of the Livorno (commander, Capt. A. Abate). The disappointment was bitter. The men couldn’t believe that the Division would have left them in the lurch. A mortar company was a joke of a reinforcement in those conditions.

Anyway, the 81 mm mortars were set up on Colle Frumento, a nearby hillock. During the day the mortars opened fire on enemy objectives on several occasions. The unit was well led and well trained. It managed to escape encirclement and destruction on the following day. Leonardi went personally to Col. Martini’s HQ post, to further clarify the situation and beg for more reinforcements. The Colonel was very sorry, but he was unable to pour more troops into the battle.

The other two battalions of the 34th Regiment detached from the Regiment and assigned to other tasks elsewhere. Leonardi remarks on the disastrous mistake of splitting up the Regiment, as it prevented a build-up of striking power that would perhaps have allowed the Italians to retake Gela.

The Night

At nightfall, the Battalion was informed that the other pincers of the Axis counterattack had been driven off with heavy losses. At that point, it became obvious that the all-out counterattack had failed, but the Battalion still was anxiously awaiting reinforcements. Gela was just a few hundreds of meters south of its positions.

At 10:30 pm, an exchange of shots alarmed the left flank of the Battalion (held by 9th Company). A few American reconnaissance or raiding parties had tried to pass it and some elements had managed to infiltrate the Company’s rear before being repulsed. 9th Company had some casualties.

At midnight, the last dreams of victory vanished. The order came to withdraw the Battalion to Mount Castelluccio and hold the hill at all costs against any enemy attacks for the following day. It also allowed the rest of the Livorno Division to disengage, then reconstitute a defensive line farther north.

Though extremely disappointed and embittered, having to evacuate the battlefield they had conquered with the loss of so many comrades, the troops marched back to their start line. The seriously understrength 9th Company was left at the Gela roadblock as a rearguard.

As they were retreating to Mt. Castelluccio, they heard the uproar of battle coming from the positions they had evacuated. 9th Company was under attack. The Americans were coming to finish off the depleted Battalion, regain the lost ground, and secure a larger perimeter to the beachhead.

After approximately one hour of fighting, 9th Company, outflanked and running short of ammo, either escaped to join the Battalion on Mt. Castelluccio, or scattered in the darkness.

In his book, Leonardi praises the fine and effective American night combat training. In night actions, they usually showed a high fighting ability, skillful surprise, exploitation, and tactical proficiency. It was the result of a thorough and intense training with tactical and operative success as the prize. This special ability contrasted with the sad and absolute inferiority of Italian regular infantry in night combat. In the Italian Army, night combat was considered to be an “exceptional” situation and as such, scarcely taken into account!

On Mt. Castelluccio, there still was the 155th Bersaglieri Motorcycle Company, or rather, the few remnants of it. The skeleton Battalion took a hastily arranged defensive position on the hill.

The End

Just before dawn, July 12th, 1943, a brief but crushing artillery barrage fell on the hill, “with telling effects” as the US official history remarks. Field guns, as well as naval guns, lobbed hundreds of shells at the Italian positions wreaking havoc among them. When the barrage ceased, US infantry came up, attacking frontally first, then outflanking and encircling the Italian units.

Image of dead Italian soldiers from the Battle of Gela.

At 7:00 am, after a desperate fight, the enemy spearheads were 50 meters away from the Battalion HQ. The surviving elements became overwhelmed by the attackers and subsequently captured.

After 24 hours of bitter struggle, the valorous 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment, no longer existed.

70% of the Battalion’s initial strength was dead, missing or heavily wounded. That was the blood price paid for the clash between flesh and iron.